The director of "The French Connection" and "The Exorcist" is still capable of pushing us where we don't necessarily want to go.

William Friedkin

William Friedkin“I view it as a piece of material that was challenging to me, and I thought would be challenging to audiences.”

A statement like that coming from most moviemakers might leave you feeling dubious: ‘What do you know about “challenging,” fella?’

But this is

William Friedkin talking, the man who made

“The French Connection,” “The Exorcist,” “Cruising,” and

“To Live and Die in L. A.,” among others. So when he talks about taking moviegoers places where they’ve never been, well, you pay attention.

At nearly 77 years old, Friedkin has found new ways to dare and provoke in

“Killer Joe,” a hair-raising and darkly funny film, which opens in Portland on Friday, August 31, and is based on a play by

Tracy Letts which, in turn, says Friedkin, was based on a true story.

“Tracy originally read this story in a newspaper,” the director explains in a phone interview. “A father and his son in Florida hired a hit man to kill their ex-wife and mother for a very small insurance policy. So when you ask what’s at the bottom of it, what it’s ultimately about, the answer is greed and the extreme lengths that some people will go to to get out of their unbearable situations.”

Letts transposed the story from Miami to Dallas, turned the hit man into a dirty cop, and turned it into something as horrifyingly and disturbingly human as a Greek tragedy about a morally corrupt family.

Friedkin saw the play some time ago, before directing the film of Letts’ play

“Bug,” and then he heard from the playwright that he’d adapted “Killer Joe” for the screen. Friedkin wanted immediately to make it, but there were problems. The film is filled with blood, profanity and depraved sexuality, and would present real problems with the movie ratings board (who, finally, slapped it with an

NC-17, its most restrictive designation): how would you finance such a thing? And who could play the seductive, sociopathic title character -- a cop who hires himself out for murders and has a taste for teenaged girls?

Money was the first hurdle. “Obviously,” says Friedkin, “no major studio was going to do anything like this, no matter who was in it. So I had to go to independent producers. I went to Nicolas Chartier, who produced ‘The Hurt Locker.’ And he’s sort of a courageous guy with a number of such projects. And he does commercial sorts of things so that he can pave the way for things like ‘Hurt Locker’ and this film. And he picked up on it right away.”

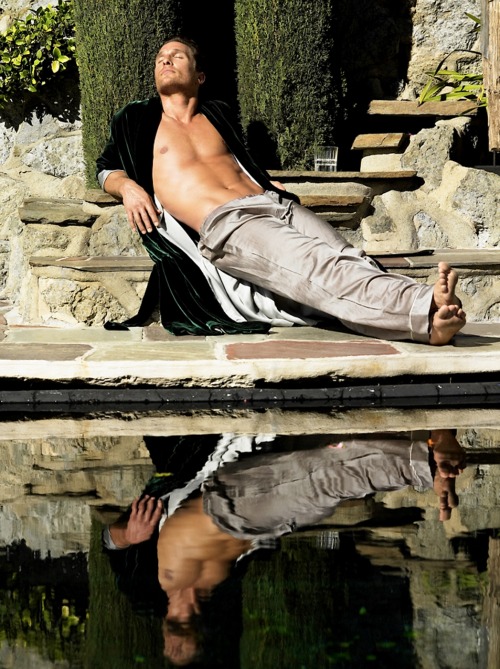

Matthew McConaughey in "Killer Joe"

Matthew McConaughey in "Killer Joe"But that still left him with a hole in the middle of the film. One night, Friedkin was watching a TV interview show and saw, of all people, Matthew McConaughey, talking about his life. “He wasn’t the first guy I thought of,” Friedkin confesses. But I was very impressed with him. I didn’t know too many films he’d made before. I remembered him from (2001’s) ‘Frailty.’ And it occurred to me that he would be exactly the right sort of guy to play Killer Joe. Not some gruff old grizzly bear, but a really charming guy, good-looking, and unexpected.”

Friedkin reached out to McConaughey, and was, at first, rebuffed. “Matthew didn’t care for it at first at all,” he remembers. “He had no interest. But then he started to think about it, and after a lot of thought he realized the dark humor of it and the truth of it. And so he said he’d like to meet with me. We met, and we had about a two hour meeting, and we were on the same page, and we went ahead.”

As it happens, “Killer Joe” comes in the midst of what we might think of as the Summer of McConaughey, with the actor providing real energy, wit and strength in “Bernie” and “Magic Mike” prior to “Killer Joe,” in which he’s joined by Emile Hirsch, Gina Gershon Thomas Haden Church, and Juno Temple. Friedkin says that he’s not terribly surprised to see an actor best known for light comedy turn out capable of something deeper. It is, he explains, a matter of technique.

“A good actor,” he says, “has to be able to go inside himself or herself, into his or her own psyche, to find the character that he or she is playing inside themselves. They’re not putting on masks, per se. But even if they’re playing Quasimodo or Hitler, you have to find that character somewhere inside yourself. You have to find those triggers which, when you use sense memory, will bring you back to those moments when you were angry or afraid or loving or threatening. You have to find those emotions in yourself.”

Over the years, he continues, he’s developed a sense for when an actor is really probing and delivering something honest, as well as strategies to help an actor who isn’t going deep enough find something true in a performance.

“When I see an actor just putting on an act, so to speak, and not becoming the character, I’m out of the show, I don’t believe it,” Friedkin says. “So before I cast someone in a film I’ll spend quite a bit of time with them, individually, and learn as much as I can about them, about the things that they’ve experienced that trigger certain emotions. And then, if necessary, during the shooting or even in rehearsal, I’ll call upon those things, very casually. I imagine it’s similar to the way a psychiatrist works. You’re calling on emotions that you know the actor has experienced so that they can draw on those in creating the character. And then, when you get on the set, you have to provide an atmosphere where the actors feel free enough to create, free enough to draw on their sense memories and not feel like they’re being judged.”

In a way, Friedkin speaks from personal experience when he talks about the freedom from being judged. Along with the likes of Francis Ford Coppola, George Lucas, Martin Scorsese and Brian De Palma, he was a lynchpin of the generation of so-called movie brats who remade Hollywood in the early ‘70s, that golden era between the death of the old studio system and the rise of the blockbuster movie.

William Friedkin directs Emile Hirsch and Juno Temple in a scene from "Killer Joe"

William Friedkin directs Emile Hirsch and Juno Temple in a scene from "Killer Joe"As Friedkin recalls, “I guess you’d have to say it was a special time, because so many people think that it was. Having lived through it, I can certainly say that it wasn’t that we had a lot more freedom than there is today. Several things were different. The guys who ran the movie studios were interested in all kinds of films, not just one kind of film. Not simply comic books or video games as movies. They were interested in all kinds of stories, they would take chances. And films cost a lot less money to make then. A lot less. So they could take those chances.”

At the same time, he says, it wasn’t like the keys to the studios had been handed over to a bunch of lunatic kids. “We were all watched very closely,” he says. “We weren’t given a totally free hand by the studios. They were all over us, making sure we came in on budget, on schedule. But they did allow us to undertake themes that were clearly different. Nobody knew we would make hits going into it. But studios were more interested at that time in challenging audiences. They weren’t interested in sequels or remakes. They were much more interested in, well, frankly, trying to replicate the success of ‘Easy Rider.’ They got the feeling that us young guys knew what the hell we were doing. And, frankly, we didn’t!”