Paul Thomas Anderson's tale of a man drawn into a quasi-religious cult is puzzling and provoking, with remarkable performances at its heart.

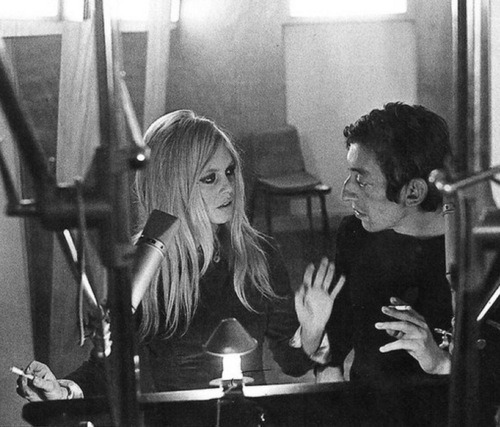

Joaquin Phoenix in "The Master"

Joaquin Phoenix in "The Master"“The Master” is cool and puzzling and almost feels more like a novel than a movie.

Writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson came onto the scene as a brilliantly gifted scamp of a storyteller, with the portraits of underground culture “Hard Eight” and “Boogie Nights” and the web-of-life epic “Magnolia.” But since then he has moved away from familiar narrative forms, first in “Punch Drunk Love,” then in “There Will Be Blood,” the last of which, in light of this new film, seems the dawn of a new phase in its maker’s art.

Like “Blood,” “The Master” concerns a strong, charismatic man determined to reshape the world no matter the personal costs. Like “Blood,” it is a film in which big ideas are chewed over but not necessarily digested, in which the world is slightly distorted to accommodate large and even grotesque characters, in which the accumulation of episodes weighs more heavily than the ‘through line’ of a ‘plot.’ It vexes and dares, it frustrates and goads, but it is powerful and singular and doesn’t leave your mind easily. It’s not as appealing, at least on the surface, as Anderson’s early films, nor does it wallop you like “Blood.” But it is something, you must admit that.

Joaquin Phoenix, back from his bizarre decision to shut down his career, plays Freddie Quell, an alcoholic, emotionally troubled seaman who finishes his service in World War II and finds himself unable to reintegrate himself into society. Adrift, he winds up aboard a yacht commanded by Lancaster Dodd (Anderson staple Philip Seymour Hoffman), a man of mysterious authority who is engaged in rethinking ideas of human psychology, history, and self-empowerment. Quell, who, in fact, needs quelling badly, is drawn into Dodd’s world, seeking to silence the demons in his head and striving to gain status among the writer’s traveling cohort of family members and apostles. But Freddie’s troubles may be too profound for any cure to avail, and Dodd’s work might not be able to offer him, or anyone else, credible answers.

Dodd is, plainly, a version of L. Ron Hubbard, author of “Dianetics” and founder of the Church of Scientology. But “The Master” isn’t a critique or expose. Yes, there are passages in which it seems that Dodd’s work is a sham, but there are also moments in which true believers profess their faith, and nothing that we see distorts the actual legal and doctrinal struggles faced by Hubbard and his followers during the period the film depicts. There will (probably) not be lawsuits.

Besides, the focus isn’t on the spiritual movement so much as the relationship between off-kilter Freddie and grandiloquent Dodd, the itchy, gaunt acolyte and his robust and Olympian master. Phoenix is almost perversely out of sync -- gangly and twitchy, speaking out of one side of his mouth, hands on hips inside-out, arms akimbo like a scarecrow. The forces inside him have gnarled and twisted his form. Just seeing him on screen makes you shift back in your seat.

Hoffman, on the other hand, brings a grand Falstaffian quality to Dodd, a fondness for food and flesh and thrills and ideas, an outsized confidence camouflaging a sometimes thunderous temper, a blend of certainty and doubt, a need to control all of those around him while giving them the impression that they command themselves. Orson Welles would’ve loved the guy.

These two herculean performances more or less wipe everyone else off the screen, and Anderson knows it. He’s got Amy Adams as Dodd’s missus, and Laura Dern as a significant devotee, both small roles, really, and there are very few other faces you might recognize. That lack of familiar faces makes it easy for him to immerse us in the post-war era of skirts and suits and big cars and no-tech living. Like the blasted-out landscape of “Blood,” the sparsity of “The Master” allows the two lead actors and the various competing ideas to play out against a relatively clean backdrop.

In speaking of the novelistic quality of the film, I specifically refer to the sense that, like Tolstoy or Dreiser or Bellow, Anderson is deploying characters and events in an effort to give shape to ideas. There’s nothing prosaic about the filmmaking, however, which is conceived in sequences of motion and light that sometimes recall the abstraction of Terrence Malick rather than the hopped-up energies of Martin Scorsese or the jazzy flow of Robert Altman, to name two of Anderson’s chief influences. Gorgeously shot by Mihai Malimare Jr. (who has photographed Francis Coppola’s last few films), with a spooky and compelling score by Jonny Greenwood, it’s exquisitely made. Anderson may be thinking like a writer, but his movies are movies.

But they are not always warm movies, and the aridity of “The Master” is, finally, its most lingering impression. It’s a film you admire, with two powerhouse performances, but it’s aloof and self-involved and eccentric. “Blood” was a head-scratcher, yes, but it galvanized, if only through the strength of Daniel Day-Lewis at its heart. “The Master” doesn’t have the same magnetic power, but it does excite you at the prospect of Anderson’s future. Once upon a time people talked quite seriously about the “Great American Novel,” a chimerical blend of intelligence, entertainment and import that would forever change and define literature. Anderson, god love him, seems determined to make the “Great American Film.” “The Master” isn’t it, but you come away from it with the sense that may be on the right path.

(137 min., R, TBD) Grade: B-plus