Fine performances and overwhelming film craft tell the story of a woman who leaves a secure home for a passionate affair.

Tom Hiddleston and Rachel Weisz in "The Deep Blue Sea"

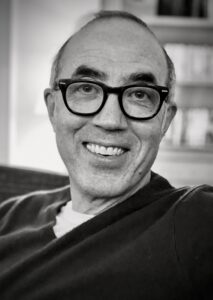

Tom Hiddleston and Rachel Weisz in "The Deep Blue Sea"There are filmmakers -- precious few -- whose artistic touch and temperament are recognizable in just a few seconds of footage or a few moments of sound. The English director

Terence Davies is one of them, a true master of the medium who has made films so small and unassuming that his name is all but unknown save to the most eggheaded cinephiles.

In his best, most personal works -- which, in my view, are the coming-of-age films

“Distant Voices, Still Lives” (1988) and

“The Long Day Closes” (1992) -- Davies crafts small, cramped worlds and stifled, frustrated emotions through the use of a dark, foggy lens, long, fluent camera moves, gently muddled time lines, and, most memorably, scenes of communal singing: working class Britons of the pre-TV age (Davies was born in 1945) rousing their spirits -- amorous, religious, patriotic, festive -- by filling pubs and sitting rooms with the melodious words of Robert Burns or Johnny Mercer, expressing feelings as a group that they’re otherwise unable to as individuals.

There are two such scenes in

“The Deep Blue Sea,” Davies’ first dramatic feature in more than a decade and a relatively accessible movie that could pull him out of the shadows of the arthouse. Which is ironic, considering that, like much of Davies’ work, it is a shadowy film, laced with mournfulness, rue and pain, albeit with a vigorous strain of frequently breathtaking beauty running through it.

The film is an adaptation of

Terence Rattigan’s 1952 play (filmed previously in 1955) about Hester Collyer, a London woman who has left her stodgy older husband to live with a fiery younger man. Hester has forsaken privilege and security (her husband is a judge and a Lord) for passion and risk (her beau is a World War II flying ace with no job prospects). Lost in love and in the labyrinth of her choices, left alone in a dreary flat on her birthday, Hester undertakes a suicide attempt, which starts the movie and sparks a weekend of confrontations, revelations and resolutions.

Filling the roles, almost ideally, are

Rachel Weisz, sensual and knowing as Hester,

Tom Hiddleston, rakish but self-doubting as her lover, and

Simon Russell Beale, stuffy and mother-cowed as her husband. (

Barbara Jefford has a marvelously acrid turn as that mother, by the way.) It’s no insult to Davies or the film to suggest that these players are so deft as to make you think they’d honed their roles during a long stage run; not a note in any of their performances is excessive or misplaced. They maintain the decorousness befitting the post-war setting while conveying earthy human impulses -- lust or anger or righteousness or pity or regret -- with modern vigor. It’s a tiny ensemble, but it’s splendid.

And splendid, too, is Davies’ direction. We slip in and out of time, now in bed with the lovers entwined as in classical statuary, now in a choked, polite confrontation between estranged spouses, now in a station of the Underground waiting out a Nazi bombardment with an unsteady chorus of “Molly Malone,” now watching outside a phone box as Hester offers the whole of her heart in exchange for next-to-nothing. From the opening frames, in which children play in the bombed-out wreckage of a London home, we are in a master’s hands. “The Deep Blue Sea” isn’t a big or bold or conventionally ambitious film. It’s only a superb one -- which, I fear, may not be enough to garner it the attention it deserves. Feel free to prove me wrong.

(

98 min., R, Cinema 21)

Grade: A-minus